One of the "secrets" of advancing towards mastery in chess, as in many other disciplines, is that the more advanced you get, the more you should be thinking for yourself in order to make real progress, not just uncritically following other people's recommendations. In chess, I would say that this process of independent thinking should start relatively early on, once you get past the initial technical subjects to be learned such as mates, identifying and constructing tactics, fundamental opening principles, and basic endgames. All phases of the game require independent thought, evaluation and judgment. At the most basic level, chess players need to answer for themselves the question why they are making each move.

The opening in particular is subject to a near-overwhelming amount of advice and provision of expert information, in the form of instructional material (books/DVDs/etc.), computer engine evaluations, and database statistics. It's certainly a good idea to take advantage of others' expert preparation and work, although it's debatable as to how much effort an improving player should put proportionally on opening preparation, versus middlegame and endgame skills.

Regardless of the total amount of effort spent on opening selection, evolving your repertoire, practice and understanding holistic concepts, I believe it's important to underline the benefits of doing serious evaluations of your opening lines (and finding new ones when necessary). This level of mental engagement will not only serve to strengthen your overall repertoire, it will - perhaps even more importantly - boost your recall and effectiveness when playing the openings in question, as you are regularly and actively evaluating different lines and their resulting positions.

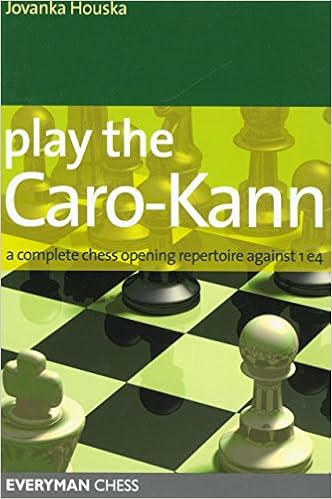

This type of active management of your openings is easily implemented using a simple database structure, which can be updated whenever you run across related material. A recent personal example of doing this on a systematic level was comparing the recommendations in Play the Caro-Kann (made easier by its e-book format) with my repertoire database and evaluating the author's recommendations. By no means did I accept all of her ideas, but studying the differences and determining why I preferred one line over another (or perhaps an entire variation) was valuable in itself. This process is also quite useful when going over individual master-level annotated games that you come across, as in the Gormally example below.

Computer tools can be quite valuable for your preparation, but also misunderstood or misused.

Database programs easily display for you the most popular and highest-scoring lines, but their statistics can be misleading in various ways. On the positive side, databases can identify shifts in popularity of particular lines and you can relatively easily pick out the important games that cause them. On the other hand, sometimes there is a quick shift away from using a particular line that means the "old" (and maybe busted) version still has a relatively high percentage result, one of the reasons why you have to evaluate lines for yourself.

- Popularity may also depend on the predicted result of the line - for example, many people may avoid a frequent drawing line as White, but perhaps you in fact want to have that as a solid weapon against higher-rated players. Other lines may be unbalancing or relatively risky, but again that may be exactly what you need, as long as you understand the trade-offs in the positions you reach.

- It matters which databases you use and why. Correspondence games can be far more accurate than OTB collections, for example, so are very valuable to theory. For practical use in OTB or online tournaments, though, it can be a bad decision to pick the theoretically "best" line if it runs 20+ moves of memorization, with multiple branching variations, and any deviation from it will likely benefit your opponent.

Engine recommendations also cut both ways. They can be helpful, mainly for checking tactics and ideas to see what responses are likely and/or best. They can also be potentially harmful to your game away from the computer. Anyone who has worked extensively with engines knows that they may come up with certain moves in the opening that may look all right in the short term, but go against the main (human) ideas for the opening and so will cause problems 10-15 moves later. One example I ran across early in my studies was in the main line of the Caro-Kann Exchange Variation, where most engines (even up until recently) evaluated 7...Na5 as best; you can even still see this on the ChessBase LiveBook with Fritz evaluations showing this as recently as 2016. However, as Fischer-Petrosian (Belgrade 1970) and others have shown, it really does not work very well in practice.

- Sometimes engine preparation can also give you a false sense of security, as illustrated by this entertaining example from GM Danny Gormally on a failed experiment in the Slav's Geller Gambit (as White). On a practical level, I found his annotations useful and adjusted my own related Slav repertoire line as a result - but only after checking other database lines and engine possibilities and looking for myself at the positions.

- Some computer products will give you a hard-coded numeric engine evaluation for literally every opening move, or you can replicate that by just running an engine. I don't believe that these are very helpful in general and to evaluate lines you will have to follow them to the end and understand the why rather than letting something like a computer's "+0.25" fully define your view of them.

In the end, perhaps it's best to recall Kortchnoi's advice (mentioned in Annotated Game #175) to just go ahead and start playing a new opening, as - if you analyze your own games - that is how you will learn best what works and what doesn't in the opening.